Whether it’s boxing out on the basketball court or making a cut on a soccer field, balance is key for athletes. And when they lose it—due to concussion or other injury—they can’t compete at full speed.

But if sports medicine clinicians had a better way to monitor specific aspects of balance, they could help their athletes get back on the field faster and more safely.

Department of Health & Kinesiology Assistant Professor Peter Fino, PhD wants to take his cutting-edge reactive balance testing out of the lab and onto the field. He and his colleagues received a Pac-12 Student-Athlete Health and Wellbeing Grant to research whether he can translate their methods into a smartphone app that’s easy for clinicians to use.

“There are already apps that monitor balance, but this would be the first to measure reactive balance, the type of balance control that you use when you’re mechanically disturbed,” Fino said. “For athletes, it’s what keeps them on their feet when they’re being pushed and pulled around in competition.”

Fino noted that return-to-play decisions for athletes have been based on a constrained view of balance when standing still. But balance generally means not falling over, even when destabilized, and that often goes untested. And this reactive balance has bigger implications for overall competitive health.

Department of Physical Therapy and Athletic Training Chair Lee Dibble, PhD, part of the research team, collaborated with Fino and other colleagues from University Athletics and U of U Health on a research paper that studied whether loss of balance is predictive of future injury in collegiate athletes.

They found that reactive balance has clinical value in predicting injury risk, and that reactive balance testing should be included in assessments for student-athletes. Athletes who return from a concussion, for example, are now at a higher risk of muscular or skeletal injuries.

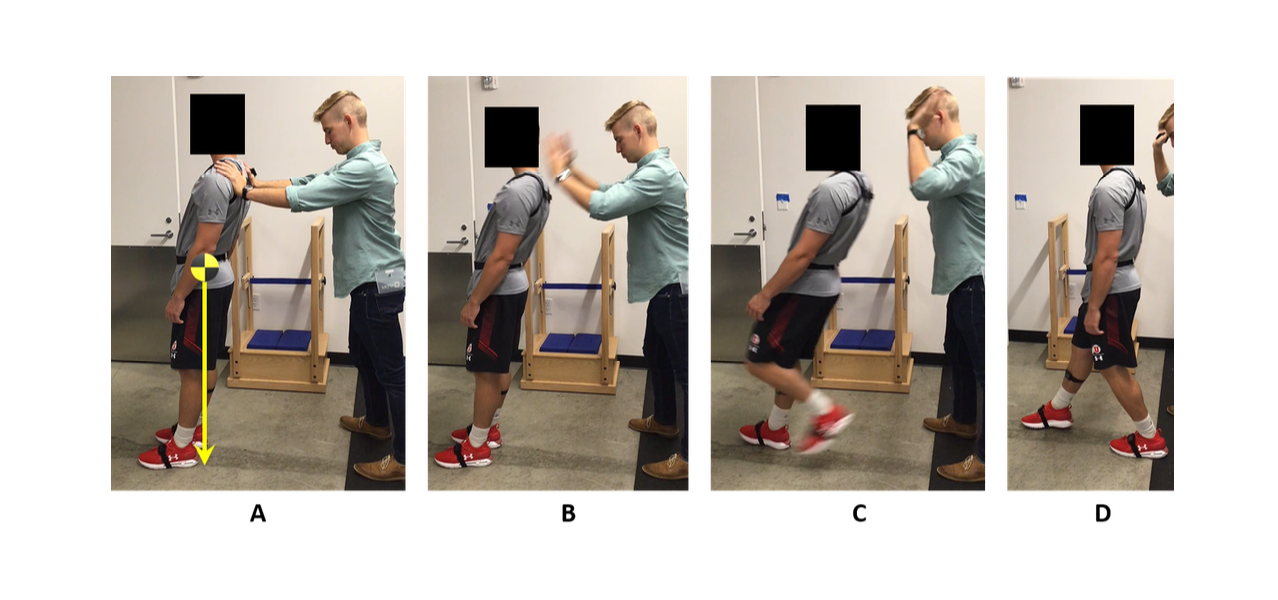

So how is balance tested? Fino and his team use sophisticated wearable sensors for biomechanics assessments. Once the student-athletes put on the sensors, they go through a series of situational tests that try to generate automatic balance responses. In many cases, they’re pushed off balance and the sensors measure their unconscious reactions.

“Right now, everything we analyze we’ve built in-house, so it’s really prohibitive to someone actually using it on the field,” Fino said. “An athletic trainer won’t have the equipment or the programs to analyze that data. We’re trying to create everything in one platform.”

Currently, Fino’s team collaborates with the University’s athletic department to conduct baseline testing on Utah student-athletes. They also want to improve balance assessments so that it’s easier to identify when athletes are ready to play after concussion.

That ties into the Pac-12 Conference’s Student-Athlete Health and Well-Being Initiative, which is a collective effort to research new ways to keep student-athletes as safe as possible.

“After a concussion, someone can exhibit any combination of impaired balance, such as swaying too much when standing, not reacting correctly when pushed, or a combination of the two,” Fino said. “That’s an important difference that hasn’t been studied yet, and this will be important in helping us decide when athletes are ready to return to play.”

To make balance easier to assess, Fino’s team wants to incorporate the sensors that are built into a standard smartphone. If they can build an app that provides baseline measurements for healthy athletes, it can alert clinicians when a student-athlete is off their game.

“We want the app to deliver prompts or recommendations on whether or not the athlete is performing well on a balance test, and if they should be monitored for proactive intervention,” he said.

Fino and Dibble envision a time when reactive balance assessments are regularly part of pre-season and post-concussion examinations. The two researchers believe that a better balance assessment post-concussion can improve treatment options and maximize recovery for injured student-athletes.

“Any athlete who shows poor reactive balance might be a candidate for some proactive, prevention based reactive balance training to try to improve those responses,” Dibble added.

“Oftentimes we don’t think that we need to be studying simple balance reactions in elite level athletes, but it can tell us a lot about underlying postural control, which is key to performance,” Fino said. “We have a one-of-a-kind partnership with the athletics department and we’re excited to take this to the next level.”